ROGERS -- Most health threats come from outside the body -- germs, viruses, toxins and such. Courtney Cook helps patients deal with attacks or weaknesses from within.

Cook is a genetic counselor, a master's degree-level expert in interpreting genetic test results for patients. Her specialty is oncology, the discipline focusing on cancer.

She is the third genetic counselor in Arkansas and the first working outside the Little Rock area, according to Cancer Challenge, a nonprofit group based in Springdale that promotes and encourages cooperation in anti-cancer efforts and provides grants.

Laboratories run genetic tests. Medical doctors analyze them. A genetic counselor like Cook explains those results in the context of a patient's symptoms and family history. She gives expert advice in understandable language.

And she may have solved the unexplained death of a child 21 years ago.

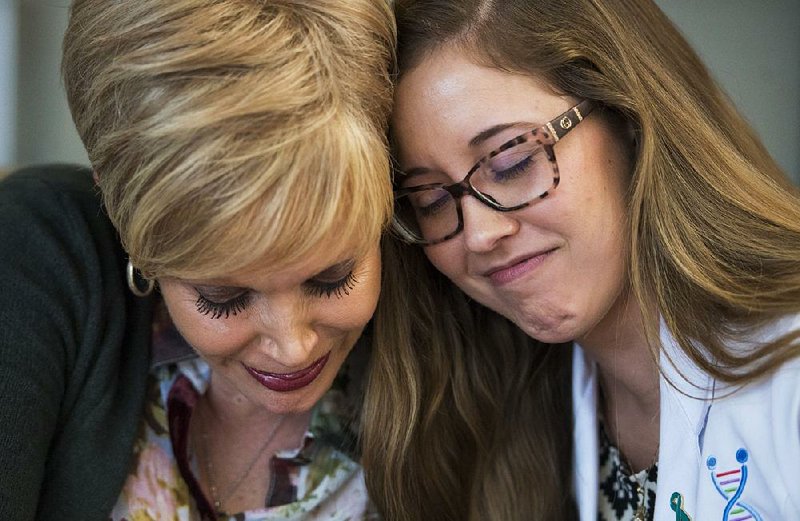

Marilyn Marshall-Miller of Joplin, Mo., was diagnosed with breast cancer in July 2016 -- one of three cousins and an aunt to develop it in a four-year period. Yet the usual test for the most common genetic link in such cases came back negative. Her surgeon wanted a more thorough check and recommended Cook by name, Marshall-Miller said.

Reviewing the family history, including the death of Marshall-Miller's child, Cook ordered another, different test. It showed Marshall-Miller has a rare genetic anomaly closely linked to breast cancer in women and prostate cancer in men.

The anomaly can also cause a condition from birth called Nijmegen breakage syndrome. The condition stunts the health and development of those born with it.

The syndrome appears to have been the cause of death of Marshall-Miller's daughter, Stephanie, in 1996 at age 5. Tissue samples taken from Stephanie, kept frozen for more than two decades, are being tested now to confirm, Marshall-Miller said in an interview Friday.

"For 20 years, I've wondered if I did enough," Marshall-Miller said of the struggle to save Stephanie's life since her daughter's birth. The test Cook had advised, which found the condition, did not exist in 1996. The mapping of the human genome, a foundation for all such tests, had not been completed yet.

During a counseling session on Nov. 30, Cook asked Marshall-Miller if she had a picture of Stephanie.

"Always. It is on my phone," Marshall-Miller said. "Courtney pulled up pictures of children of people with Nijmegen breakage syndrome, and they looked like Stephanie's brothers and sisters.

"I went to the chapel and cried," Marshall-Miller said.

Then she called family members and Stephanie's pediatrician in Joplin, who had also struggled mightily to save the child's life. She cried, too, Marshall-Miller said. After more than two decades, they have what appears to be an answer.

In other cases, a genetic counselor might see someone who is going to one doctor for kidney trouble and also to a skin doctor for facial polyps, Cook said. There is an inherited illness that can cause both those conditions, she said. That same illness can lead to cancer. Cook's job would be to recognize the possible link and recommend the right test to find out whether the conditions are linked, all while keeping the patient and the patient's doctors informed.

Different genetic tests look for different specific mutations, Cook said. Ordering the right test requires knowing quite a bit about the patient and the available tests, she said.

Cook has seen about 200 patients since she opened her office doors in September. Most appointments are about 90 minutes long, she said, because she must carefully review family and personal history.

Insurance has covered the full cost of genetic testing for about three-quarters of the patients she has seen, Cook said. About 10 percent of the remainder have paid less than $200, she said. Marshall-Miller said that charities such as cancer foundations will also help pay for such testing.

The counselor doesn't always recommend testing, Cook added.

Cook received her degree from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Cancer Challenge had looked for someone like Cook since 2010, Executive Director Erin Rongers said.

The nonprofit set finding a genetic counselor as a priority, provided a $50,000 grant toward that goal and worked out the details of Cook's cooperation among cancer treatment centers in the area. Cook works out of an office at the Highlands Oncology Group in Rogers but sees people referred by cooperating clinics throughout the region.

"It's been a gap in our community service for a long time, and then, quite suddenly, the right players were in place," Rongers said of finding Cook and the necessary support network.

Counselors like Cook are in very limited supply, Rongers said. There are 30 schools teaching the discipline in the country, she and Cook said, and each graduates about six to eight students a year. Cook spent time in Northwest Arkansas as a student at UAMS and was familiar with the Cancer Challenge, she and Rongers said.

Dr. Bradley Schaefer, director of genetics at UAMS, described genetic counseling as "a very intense job."

"It's half science and half social work and psychology," he said. "Sometimes you have powerful, potentially painful news to tell someone."

A counselor may need to tell a patient that a flaw or mutation in his genes will lead, or very likely lead, to cancer and that other members of the family also need to be tested.

"That is not the type of thing you can tell someone and then tell them to go home and have a nice day," Schaefer said.

"Genetic testing helps direct almost all cancer treatment these days," he added.

The right tests can help identify the best medicine to use, the right doses and even predict possible side effects in cancer and other conditions, he said. The whole field is ever-changing, he said.

Since the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2001, genetic testing has progressed at an exponential rate.

"The sky is the limit," Schaefer said. "For instance, there are studies now looking at the implications of doing whole genome sequencing on the newborn screening blood-spots. Think about what that means. By the second day of a person's life you can know their whole genetic makeup and all that entails. Of course genetic counseling will be critical to interpret this complicated information to people."

Clear, inescapable results are the exception, Cook said, but the patient is better off knowing the possibilities even in the worst cases. Then he knows he needs to have himself screened frequently to catch any cancer as early as possible, which could vastly increase the prospects of successful treatment, she said.

"If you have a predisposition, it exists whether you test for it or not," Cook said.

Her job does not end with telling a patient what health threats he faces. Cook also works with doctors to develop a plan for regular tests and changes in the patient's lifestyle if they are needed.

"I'm proactive. I'm a very proactive person, and that is the most important thing," Cook said.

Testing many times reveals a mutation that may or may not be harmful. That needs to be assessed in light of the patient's history, Cook said.

She compared ambiguities in gene testing results to misspellings. The purpose of genes is to carry messages, so to speak. Genes do not have to be perfect to do their job, Cook said. A "misspelling" might not be important as long as the message is understood.

Someone reading the word "color," for example, knows the word and knows when it is spelled correctly, she said. Someone reading the word "colour" might realize that is either the British spelling or a misspelling, but he can still read the message containing the word with a high degree of confidence.

But the misspelling "kolor" is also the name of a virtual-reality company, a fashion line and a radio station, and its intended meaning may be misinterpreted.

"The cases where there is a clear and positive 'misspelling' are about 10 percent" in the world of genetic testing, Cook said. "The ones that are negative for a mutation are about 60 percent. The remaining 30 percent are 'variants of unknown significance.'"

Narrowing down what is unknown by looking for related symptoms, family history or any other relevant factors is part of her job, she said.

Marshall-Miller has a healthy, grown son who will now be tested to see if he carries the same condition. All her relatives who may have inherited the condition have been informed, she said.

Not only do they know to be screened for certain types of cancers more often, they also know what kind of cancer tests are best.

"Something that wasn't on our radar ever is suddenly all over our radar," Marshall-Miller said. "Genetic testing is not the wave of the future. It is the necessity of right now."

Metro on 12/31/2017