COLUMBIA — After nearly 60 years of life-saving discoveries, the University of Missouri's Research Reactor, or MURR, in short, is getting an upgrade.

MU officials announced Wednesday the creation of a NextGen reactor, capable of doubling the existing reactor's output.

The new reactor, officially called NextGen MURR (MU Research Reactor), will be a collaboration between the university and a consortium that includes Hyundai Engineering America, the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI), Hyundai Engineering Company and MPR Associates, according to a news release.

According to past KOMU 8 reporting, the NextGen MURR project will cost the university $1 billion and is expected to open in the next eight to 10 years.

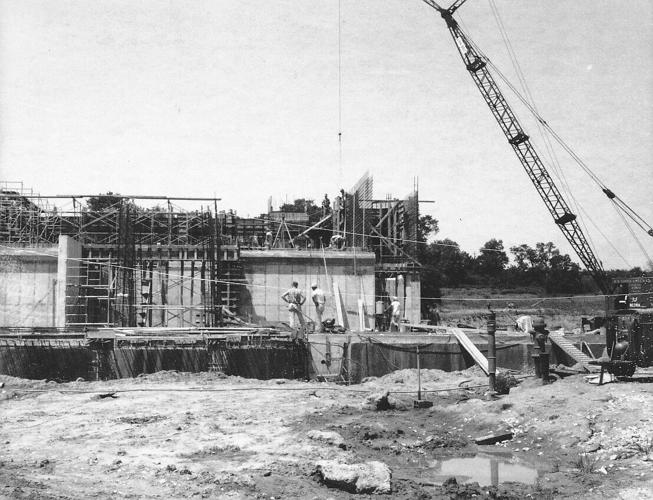

A photo of the University of Missouri's research reactor being built in late 1965.

MURR's history

MURR was built in 1966, with design similarities close to the space-age aesthetic of the era.

According to MU's website, President Dwight D. Eisenhower's call for a peaceful use of the atom, as nuclear powers grew globally, inspired then-university President Elmer Ellis to begin talks on creating a research reactor.

Progress being made on MURR, July 2, 1964

In 1959, Gov. James T. Blair signed bills to fund the reactor's creation.

According to the university, MURR was initially allowed a license for five megawatts of production, but later doubled to 10 megawatts, making it the highest-power university research reactor in the nation.

"We've built the model on how to do this and how to do it right and safely and reliably," said Uriah Orland, the MURR director of communications. "We're the only reactor in the world that operates 24 hours a day, six and a half days a week, every week of the year."

The main column of MURR being constructed, Sept. 23, 1964.

MURR has since allowed students, faculty and researchers to use the facilities to discover life-saving elements at a reliable rate.

"We are the only ones that have this operating schedule," Orland said. "Doctors have patients who have cancer, they can know that they will have treatments."

Orland said the reactor began creating radioisotopes in the '90s. Since then, MURR has grown to be an integral part of the medical landscape.

A photo of the University of Missouri's research reactor being built in late 1965.

"We are the only producer of four medical isotopes used in cancer treatments," Orland said. "They're used to treat thyroid cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer and liver cancer."

One of these radioisotopes, known as Lutetium 177, is a core piece in the only two FDA approved targeted radiotherapies. These are just as effective but less dangerous than chemotherapy, Orland said.

Finishing touches are being done on MURR, October 21, 1965.

"Those drugs use a targeting molecule that seeks out a cancer cell and only targets that cancer cell and leaves the healthy tissues in the body alone," Orland said.

Orland suggests the reactor means far more for patients across the country, rather than just for the students researching.

"That's what these drugs bring. They bring hope to the patients," Orland said. "They bring, you know, extended life, less side effects."

MURR is completed and pictured on May 29, 1966.

The future

A 1960s reactor has its limits.

Orland said the opportunity for more research, production and discovery lies beyond what MURR can currently handle.

"Having a reactor that is more powerful allows us to potentially make different isotopes," Orland said. "It also ensures that we're able to make the current isotopes in a different design than the current MURR."

With the addition of the NextGen research reactor, Orland said he hopes the legacy of MURR can be carried on to a much larger extent.

"We're doing this, it's happening," Orland said. "It's a really exciting time because it's this is the first step to make a vision and an idea a reality."

Both reactors will be able to run at the same time, multiplying the output of life-saving elements like lutetium 177.

"It expands and expands and expands the impact that the reactor will have for Columbia, for the University of Missouri, really making Columbia the Nuclear Science Center of America, which is it's amazing," Orland said.